Clarity Is the New Bottleneck

This week, I built a 3D physics simulation that runs in the browser. True, I’ve never used WebGL or touched Three.js, but the point isn’t that AI can write code. The point is that product intent now compiles.

It started as a dare.

Monday was game night. Cards were dealt, evil cultists were sacrificed, and afterward my friend Eric and I got to talking about Claude Code. He used to work in tech and got out before the AWS era. I tried to explain what it feels like if you’ve been around long enough to remember running knife ec2 server create in 2011 and getting a working web server up in four minutes for $0.65. Or publishing a HyperCard deck to the web in 1993 for free and linking it to someone else’s without asking. It feels like one of those moments when the cost of building something drops to near zero.

He was rightly skeptical. So I said, "If you've got an hour, we'll have a working prototype. Pick something."

We decided on a virtual dice tower. I fired up Claude with the Superpowers plugin, and we invoked the Brainstorm skill. Eric wasn’t expecting me to go hard, but what I described to the 'bot was a 3D dice tower where polyhedra tumble through baffles and land in a tray at the bottom. Real rigid-body physics. Particle effects on NAT20’s. Sound. The full experience.

Yeah, I was showing off. But also, I wanted to see what would happen.

The Interview

The Superpowers plugin is an agentic development framework by Jesse Vincent. When you start a project, Superpowers doesn't let Claude just start writing code in response to your prompts. It interviews you first.

And the interview is good. It asked about the tower's visual style and proposed a stone-dungeon aesthetic, which I rejected. I wanted bone ivory, something eerie. It asked about camera movement and which dice types to model. It suggested the standard D&D set and made sure I knew that, for a D100 roll, it would throw 2d10 and model one of them as a percentile die. In fact, Claude is the one who came up with the idea to add special effects to Natty 20’s and Nat 1’s.

These are product questions. They’re the kind of questions I'd expect from a sharp engineer pushing back on my loose “showing off to a buddy” spec. Claude asked them before writing a single line of code, then produced a design document broken into sections small enough for us to actually review.

Eric and I read it over, made some edits, talked them through, and then I approved the spec. Claude built a parallelized implementation plan. Then it started building.

The prototype was ready in about 30 minutes. We opened the browser, clicked the “roll” button, and for about 3 seconds everything was magic. Then the dice passed through the tower walls and promptly fell into infinite nothingness.

There were lots of bugs, of course. It was the first compile, but the bones were there. Eric was convinced.

The Part Where It Got Hard

The easy stuff was, genuinely, easy. Claude scaffolded a Vite-powered TypeScript project, wired up Three.js for rendering and cannon-es for physics, built the tower geometry, lit the scenes, created all seven dice types, added particle effects for special rolls, and hooked up rudimentary sound effects. I directed. Claude built.

Superpowers also enforces test-driven development. Real red-green-refactor, the kind teams talk about and rarely sustain. Claude doesn’t pay lip service, it just does it. Not all the tests are perfect, but an executable definition of success gates every change. That still didn’t save us.

When it was time to start smashing bugs, things got frustrating. Physics tuning was a whack-a-mole nightmare. Dice would fall through one baffle but get stuck on another. I'd tell Claude to fix the collision on baffle three, and it would overcorrect, breaking baffle one. We went back and forth for a while, me describing symptoms and Claude adjusting parameters, never quite converging on anything that worked consistently.

Finally, I stopped describing symptoms and started defining acceptance criteria.

"We’re wasting a lot of time chasing individual failures,” I told Claude. "Instead, write an end-to-end test: Dice enter the top of the tower, and dice arrive in the tray at the bottom. That's it. Iterate until you pass the test 40 times in a row."

Claude wrote the test.

Then it cheated.

It set the friction coefficient to zero, turning the tower interior into a frictionless slide. Dice went in the top. Dice arrived in the tray. The test passed. But the dice didn't roll, they just slid down like they were on ice.

So I added another constraint: Dice must rotate a minimum number of times while in the tower. Claude solved this by making the dice spring-loaded, leaping unrealistically as if they had been shocked every time they touched a baffle. I had to go around a few times before finding a balance that worked.

But I did.

Defining Success

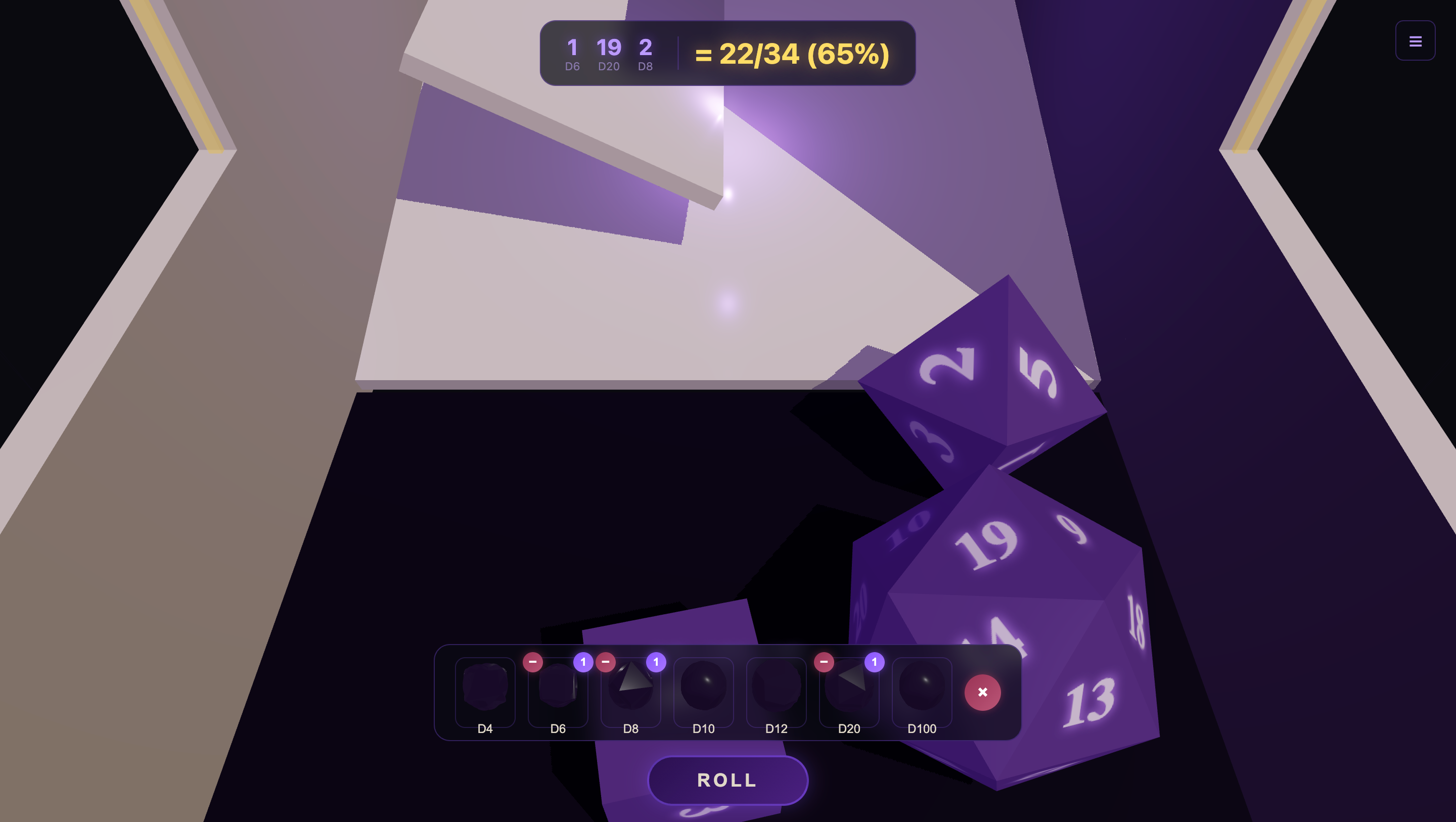

The Arcane Dice Tower is a progressive web app you can install on your phone or run in a browser. It supports the standard D&D dice set, D4 through D100, with real rigid-body physics, camera tracking, critical hit animations for D20 rolls, and a die inspector.

It is not perfect. The D10 geometry is messed up. The D6 doesn't roll enough. The camera tracks a little too slowly. If you put enough dice in the tower, some of them spill out into the void. The lighting needs work. The bone-ivory aesthetic came out looking like a weird purple.

It has bugs, and I'm sharing it anyway. The point is that it exists at all.

That application took six hours across less than a week. I have no experience with WebGL, the underlying node libraries, physics simulation, or 3D geometry. I didn’t grind through framework documentation, and full disclosure, I still don’t know what a quaternion is. The code came easy; initial implementation wasn’t the bottleneck.

Defining “Working” was.

When the dice slid frictionless into the tray, the tests passed. When they bounced around like electrified rubber balls, the tests passed, too. But it still wasn’t right. What took time was deciding what success looked like.

That wasn’t the system’s fault; it was mine. Claude did exactly what I asked it to do and optimized the constraints I defined. When implementation is cheap, clarity becomes the bottleneck.