When the Lights Go Out

Say what you will about Twitter and its impact on our culture, but you can't deny that the people building it acted with passion and care. Since the end of October, when the company was bought out and taken private, those creators have watched helplessly as the new owners transformed the company and the project born of their dedication into something else entirely.

Before the change in management, many people working at Twitter had been wary of what the company's famously capricious billionaire suitor might do. But the reality turned out to be far crueler than they'd imagined, and conversations lamenting the destruction from current and former Twitter employees have dominated tech social media.

For many of them, this was their first Lights Out moment.

Lights Out moments are a new phenomenon brought on by the internet age. Throughout history, most people have supported themselves by expressing ideas, creating and enforcing agreements with other humans, or building and arranging tangible objects—things made of atoms. However, for those working on the internet, we can now make money by arranging electrons. And it turns out that specific configurations of electrons are extremely rewarding, and some are even extremely profitable!

But by their very nature, a pleasing configuration of electrons is a fleeting thing. As all of these Twitter employees are discovering, when you're an electron worker, all someone has to do to permanently erase your life's work is turn off the power. Lights Out.

This is not to say that it is rare or unusual for a person to see all of their efforts destroyed capriciously. But the incredible ease with which any number of phenomena can wipe them out is a new phenomenon of the electron worker. It is a bitter but necessary lesson for anyone who wants to be in tech, and I was lucky to learn it early in my career.

In 2005, I helped launch a cell phone company with a revolutionary idea: They had an app store that sold movies, TV shows, music, games, and communication tools, all from the handset. It seems passé now, but before iPhones, the concept was incredibly innovative. Unfortunately, they also tried to do it from clunky Kyocera slider phones. Amp'd couldn't even offer customers a Motorola RAZR for their first year in business.

To say it didn't work out is an understatement. AMP'd Mobile burned through $350M of investor cash in less than two years, arguably the last significant failure of the first .com era.

As the lead systems admin on their infrastructure, I routinely put in 80-hour weeks with 24/7 on-call. I spent days sleeping on cots in warehouse data centers and eating fast food in the conference room, never seeing the sun while we racked giant SAN clusters and live-migrated data. I wrote new tooling to solve problems nobody else had ever solved before, putting the best of my creativity and life into the project. Get me in the right mood, and I might tell you the story about being wrecked out of my mind at a New Year's Eve party with a half-dozen other sysadmin friends, all of us slurring into a speakerphone at a poor NOC technician about how to kill and safely restart a desynched JBoss cluster.

I was young, I was at the top of my game, and I gave Amp'd everything I had.

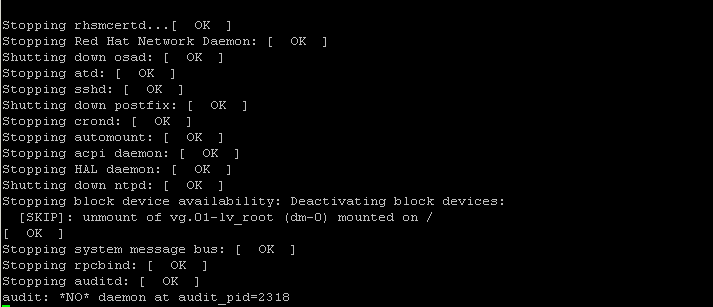

One day, they stopped paying their bills, so we just... turned the servers off and never turned them back on. All of the best work of my young career went away with a shutdown command.

I had something of an existential crisis. Seeing how fragile and fleeting my best efforts were, what were they genuinely worth, in the end? It was incredibly humbling. Did I even want to do this kind of work anymore? How much of myself could I continue to put into my career?

What did I want the impact of my life to be?

In the fifteen years since Amp'd Mobile folded up, I've been part of a few more Lights Out events and have watched others experience them for the first time. I've tried to be there for dozens of my colleagues and friends as they've wrestled with these same questions. It hasn't been easy for anyone; some have become quite bitter.

I imagine these same questions are what the Twitter alums are dealing with right now. It will be difficult for them, too. But this is a necessary step in the career for anyone who wants to arrange electrons for a living. Because the things we make, the ways we express our creativity, none of it is tangible. It can all go away with the press of a button. And we have to face that part of the bargain with our eyes open. Making something lasting of our lives is difficult, and very few of us will ever do it. But making something lasting with electrons? It might be damn near impossible.